Suffering and persecution in early Christianity

Exploring the writings of Ignatius and Justin Martyr

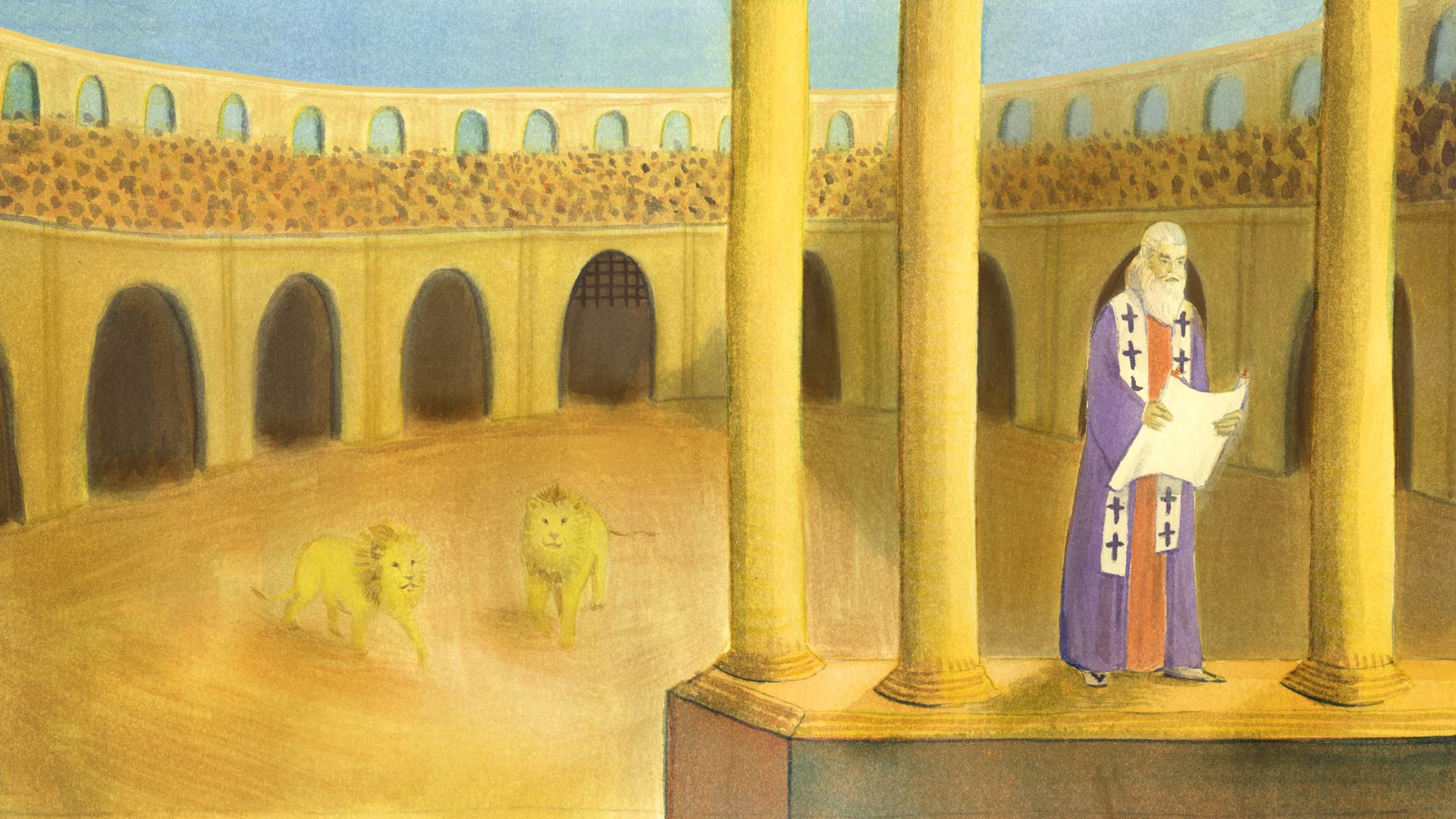

Among the many characteristics of early Christians that astonished their pagan neighbors, one of the most prominent was their willingness to suffer persecution, and even death, for their faith. The writings of three second-century figures — St. Ignatius of Antioch, the unknown author of the Epistle to Diognetus, and St. Justin Martyr — bear witness to this remarkable quality of early Christians, and they demonstrate how early Christians can inspire those of us who are heirs to their faith today.

In the early second century, Ignatius, the bishop of Antioch, wrote letters to a number of churches on the way to his execution in Rome. In these letters, Ignatius begs the churches to pray for him, but not to interfere with his impending martyrdom, which will allow him to be not simply “a mere voice,” but indeed “a word of God” (Rom. 2.1). In this, Ignatius draws upon the example of “our God Jesus Christ,” who “is more visible now that he is in the Father” than he was in his own earthly life (Rom. 3.3). Chained and escorted by a company of soldiers, Ignatius writes that though his guards only abuse him more when they are treated kindly, “[y]et because of their mistreatment I am becoming more of a disciple” (Rom. 5.1). Ignatius indeed rejoices in the closeness that his suffering brings him to God:

“The one near to the sword is near to God, and he who is in the midst of beasts is in the midst of God: only let it be in the name of Jesus Christ, so as to suffer together with him. I endure all things because he, the perfect man, empowers me” (Smyr. 5.1).

For those who face similar antagonism from Christianity’s opponents, Ignatius counsels to “allow them to be instructed by you, at least by your deeds. In response to their anger, be gentle; in response to their boasts, be humble; in response to their slander, offer prayers; in response to their errors, be steadfast in the faith; in response to their cruelty, be civilized; do not be eager to imitate them” (Eph. 10.1–2). It is by following Christ’s example, especially in face of persecution, that the truth is made known: as Ignatius writes, “[t]he work is not a matter of persuasive rhetoric; rather, Christianity is greatest when it is hated by the world” (Rom. 3.3).

The willingness to suffer seen in Ignatius is similarly attested in the Epistle to Diognetus, an anonymous second-century apology for the faith. In introducing Christianity to Diognetus (evidently a pagan of some standing), the author describes the paradoxical encounter of pagan hostility and Christian beneficence:

[Christians] obey the established laws; indeed in their private lives they transcend the laws. They love everyone, and by everyone they are persecuted. They are unknown, yet they are condemned; they are put to death, yet they are brought to life. They are poor, yet they make many rich; they are in need of everything, yet they abound in everything. They are dishonored, yet they are glorified in their dishonor; they are slandered, yet they are vindicated. They are cursed, yet they bless; they are insulted, yet they offer respect. When they do good, they are punished as evildoers; when they are punished, they rejoice as though brought to life. By the Jews they are assaulted as foreigners, and by the Greeks they are persecuted, yet those who hate them are unable to give a reason for their hostility. (Diog. 5.10–17)

The apologist illustrates this relationship between well-meaning Christians and the hostile world with an analogy, that of the soul and the body:

In a word, what the soul is to the body, Christians are to the world. The soul is dispersed through all the members of the body, and Christians throughout the cities of the world. The soul dwells in the body, but is not of the body; likewise Christians dwell in the world, but are not of the world. The soul, which is invisible, is confined in the body, which is visible; in the same way, Christians are recognized as being in the world, and yet their religion remains invisible. The flesh hates the soul and wages war against it, even though it has suffered no wrong, because it is hindered from indulging in its pleasures; so also the world hates the Christians, even though it has suffered no wrong, because they set themselves against its pleasures. The soul loves the flesh that hates it, and its members, and Christians love those who hate them. The soul is locked up in the body, but it holds the body together; and though Christians are detained in the world as if in a prison, they in fact hold the world together. The soul, which is immortal, lives in a mortal dwelling; similarly Christians live as strangers amid perishable things, while waiting for the imperishable in heaven. The soul, when poorly treated with respect to food and drink, becomes all the better; and so Christians when punished daily increase more and more. Such is the important position to which God has appointed them, and it is not right for them to decline it. (Diog. 6.1–10)

For the author of Diognetus, the way in which Christians take up their God-appointed position in the face of persecution serves as evidence that theirs is no mere human doctrine:

[Do you not see] how they are thrown to wild beasts to make them deny the Lord, and yet they are not conquered? Do you not see that as more of them are punished, the more others increase? These things do not look like human works; they are the power of God, they are proofs of his presence. (Diog. 7.7–9)

Such things served as proof for Justin Martyr, a philosopher who converted to Christianity and wrote defenses of the faith to the Emperor and Senate around 150 A.D. Previously a Platonist and admirer of Socrates, Justin became a Christian in part from seeing how Christians were fearless of death (2 Apol. 12). Interestingly, Justin maintains a high view of Socrates, holding that Christ as the logos was known to him in part, and that evil demons conspired against Socrates for teaching what was righteous and true, much as they do to Christians. Nevertheless, Justin recognizes that no one trusted in Socrates so as to die for his teaching, while in Christ, “not only philosophers and scholars believed, but also artisans and people entirely uneducated, despising both glory, and fear, and death” (2 Apol. 10).

As a Christian philosopher, Justin makes clear to the Roman authorities that Christians do not seek persecution as a form of quasi-suicide, and indeed writes his apologies so that the Romans should bring their maltreatment of Christians to an end (which would go unheeded, as Justin himself is martyred around 165 A.D.). However, Justin also makes clear that he writes out of love for the persecutors themselves, so that they might escape the just judgment of God and be brought to life. For if the persecutors do not listen, Christians “reckon that no evil can be done to us, unless we be convicted as evil-doers or be proved to be wicked men; and you, you can kill, but not hurt us” (1 Apol. 2).

These witnesses from the second century serve as an encouragement and inspiration for Christians who live with the reality of persecution, as well as those who practice their faith in safety today. For those who know persecution first-hand, these figures encourage us to recognize that the way of suffering has been well-worn from the beginning by Christian saints — indeed, the greatness of the faith was seen most clearly when faced by the world’s hatred, and their suffering was the very means by which God awakened and transformed the hearts of their pagan opponents. Among those who live in safety, these early witnesses inspire us to examine how we can accept with joy those opportunities, however small, that we are granted to suffer with Christ in our own lives each day. For it is in suffering that Christ’s glory is revealed (John 12:23–28), and if we suffer together with Him, we shall be glorified together with Him as well (Romans 8:17).

Respond:

- What do you think? You can highlight text from this article to make a comment on it or add your response below.

- Why not get together a group and talk through this issue of Word & World with our discussion questions?

Works cited

- The Epistle to Diognetus.

- St. Ignatius of Antioch, Epistle to the Romans.

- St. Ignatius of Antioch, Epistle to the Smyrneans.

- St. Ignatius of Antioch, Epistle to the Ephesians.

- St. Justin Martyr, The Dialogue with Trypho.

- St. Justin Martyr, The First Apology.

- St. Justin Martyr, The Second Apology.