Parachurch Organisations and Student Movements in Africa in the 1990s and 2020s

Introduction

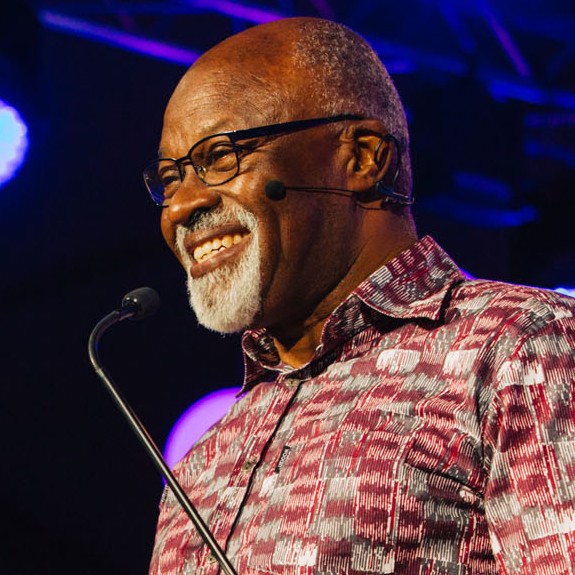

When the IFES Word & World’s editor invited me to consider reviewing and updating a paper I penned and presented at an academic conference just over three decades ago, on the role and prospects of parachurch organisations and student movements in shaping Christianity in Africa in the 1990s, I welcomed it as an opportunity to engage in discourse on the social impact of the IFES movement. The conference at which I presented the paper was a gathering of Christian mission historians, social scientists, theologians, and mission and church leaders. Convened by two centres at Edinburgh University – the Centre for African Studies and the Centre for the Study of Christianity in the Non-Western World – it considered the prospects and challenges of Christianity in Africa in the 1990s. My credentials at the conference were that of a young practitioner in parachurch and student movements.

Fortuitously, at the time of the conference, I was taking on leadership responsibility in the IFES regional movements in English and Portuguese-speaking Africa (EPSA) (as is characterised in IFES nomenclature), after twelve years of leading the work in Uganda. Reading the paper now, it is evident that the opportunity provided me the impetus to reflect on Africa’s social crisis at the time, and the potential of IFES work to form a kind of Christianity in Africa that would contribute to social progress. The paper’s objective was twofold: first, to cast an imagination of a Christianity that will contribute to social progress in Africa in the 1990s; second, to propose what contribution and what role evangelical parachurch organisations and student movements could play in shaping that kind of Christianity. The hindsight of three decades, during which I have served in different parachurch organisations and a local church (Church of Uganda, in the Anglican tradition), affords me latitude and longitudinal distance that enables me to reflect on the achievement of the visions and hopes cast then.

In this paper, I attempt to summarise the gist and logic of the 1996 paper, interrogate what informed the narrative, assumptions, and social imagination I subscribed to then, and propose a path for the second half of the 2020s into the 2030s. Since this reflection is intended for an audience interested in the place of the student movement in Africa as part of the parachurch phenomenon, I devote most of the discourse to IFES in Africa. I hope the verdict of those reading this paper three decades later will adjudge the older me wiser than the younger version.

The 1996 paper explores the role played by parachurch organisations generally and IFES student movements in Africa specifically, in shaping Christianity and consequently social change.

A Summary of the Paper ‘Parachurch Organisation and Student Movements in the 1990s’

The paper defines the parachurch phenomenon as contingent upon an understanding of ‘church’, because the prefix para- connotes the idea of being very like, connected with, or helping. It posits the church as an entity whose raison d’être is rooted in its Trinitarian origin (God: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit); with a dual relationship and mandate to God and God’s creation. It argues that church congregations and denominations are the visible expressions of this dual purpose—relationship and function—and that parachurch organisations exist to serve the local church. What distinguishes church and parachurch organisations are two parameters: structure and focus. Parachurch organisations are not structurally part of local churches and focus on aspects of the church’s dual purpose, often with distinctive ideology and methodology. The paper observes that the initiatives of the 18th and 19th century missional parachurch organisations in Europe and North America birthed the largest section of Christianity in Africa (the denominational churches). It also notes that the influx and mushrooming of most of today’s parachurch organisations in Africa was a phenomenon of the beginning of the second half of the 20th century.

The paper classifies student movements as a form of parachurch organisation, born out of the vision and work of a group of Christians, focusing their mission on students at secondary (high school) and tertiary (colleges and universities) levels. It highlights the African Evangelistic Enterprise (AEE) as an example of a parachurch organisation and the International Fellowship of Evangelical Students (IFES) in Africa as representative of a student movement. Set in the African context of both the socio-political backdrop in general and Christianity in particular, the paper outlines the origins, work, and ministry of the two organisations, and the prospects of their future work, projecting a hopeful impact on the church’s presence as an agent of social change. The paper’s broad-brush portrayal of the African socio-political context utilised Robert S. McNamara’s presentation (president of the World Bank in the 1970s) at the Tokyo Forum, 13-15 May 1991. The verdict on Africa’s socio-political and economic situation entering the 1990s and beyond is grim, characterised by growing poverty; declining economic growth; low productivity in agriculture; high population growth rates; environmental degradation; a crippling debt crisis; unfavourable terms of trade; an AIDS pandemic further depressing the economies; political instability; and the ongoing rivalry and competition for the soul of Africa between traditional beliefs and practices, Islam, Christianity, and secularism.

The portrait of the churches is mixed, according to the prognosis by Tokumboh Adeyemo, one of Africa’s eminent evangelical church leaders at the time. On the one hand, Adeyemo celebrated the church’s numerical strength due to high growth rates, its spiritual fervour expressed in indigenous idiom, and its resilience against persecution. On the other hand, the churches in Africa are plagued by divisions and disunity; a deficiency in biblical-theological depth (for “Africa not only imports Western technology but also Western theology”); a shortage of trained personnel – both quality and quantity; and a lack of visible social impact (because “the corruption and rivalry that bedevils African governments is also in the Church”). The paper explores the role played by parachurch organisations generally and IFES student movements in Africa specifically, in shaping Christianity and consequently social change.

The paper argues that in spite the short three decades of its presence in 26 countries in Africa, there was already some visible impact of the IFES movement on Christianity in Africa. This is probably due to its evangelical theological roots and distinctiveness (in contrast to the so-called liberal World Student Christian Federation (WSCF)), and its commitment to growing indigenous leadership at national levels. It points out that some of the leading evangelical personalities in the Church had been nurtured as in the Christian Unions. In some countries, notably Nigeria and Kenya, the national student movements were already initiating programmes for nurturing indigenous missionaries. The paper suggests that to harness the IFES movements’ potential for growth, impact, and the transformation of Africa for the glory of God, it would be essential to build capacity in three areas: (1) contextualised Christian scholarship and literature, to feed the minds and enrich the lives of Africans; (2) new models of missionary work, to develop a strong and able indigenous missionary force to reach Africa and beyond; and, (3) intentional integration of faith and life, to produce a disciplined work-force of men and women of integrity, who would contribute to arresting the social decay in Africa’s public life.

The paper commended a strategic agenda that would engender three things: first, a critical analysis of the needs and aspirations of Africa in general and Christian Africa in particular, to produce contextual and transferable models; second, institutional and leadership capacity building for upgrading accountability systems, building synergies with other organisations with congruent ethos and harnessing the leadership potential in the churches; and, third, making research-based planning a priority for consolidating gains from the past and developing strategies for the future. The paper recommended that, in the immediate term, biblically informed actions should be undertaken to redress waning family stability, the dearth of relevant contextual literature, and growing poverty, ignorance, and poor health in African churches and societies.

A Conversation with the 1990s Perspective: Reimagining IFES Student Movements in Africa in the 2020s

Three decades since the publication of my paper, reveals a troublingly similar portrait of Africa’s socio-political context and the state of Christianity in Africa. Christianity has continued to grow as the dominant faith across the continent south of the Sahara, but it social impact is dismal. Africa’s socio-political malaise remains, with faces writhing “in anguish from civil wars, drought, the dictators’ boots and poverty.” The African socio-political and economic world is swelled with men and women who are products of the IFES movements in many countries; yet, injustice, violence, and corruption continue to characterise the government and society. Eminent African theologian Emmanuel Katongole poses the question well:

Why, despite the growth of Christianity and the social activism of the churches, Africans are in general 40% worse off than they were in the 1980s. One then wonders: What accounts for the dismal social impact of Christianity in Africa? Why has Christianity, despite its overwhelming presence, failed to make a significant dent in the social history of the continent?

A cursory survey of the current state of IFES national movements in countries will show that there has been growth in the number and size of IFES national movements south of the Sahara. This begs the question: In light of the prognosis I painted in 1992, why is the social impact of Christianity dismal despite the growth of IFES movements in Africa over the last three decades? Were the assumptions lacking in depth? Were my proposed strategies and agenda impotent for shaping a Christianity with a social conscience? Was the failure internal, due to the ethos, logos, and pathos of the IFES? Or was it due to IFES movements’ failure to pursue the strategy and agenda that was recommended then? There may also be other questions that the apparent contradictions in the context invite us to grapple with. I contend that asking the right questions is more critical than prescribing strategies and agendas for action.

I am persuaded that the crux of the matter lies with the assumptions that informed my prognosis: first, about African states as constructs for ordering power patterns for the common good; second, that evangelical Christianity would provide moderating influence towards the common good; and, third, that IFES distinctives and ethos embodied the corrective to nominal Christianity that I judged impotent in the face of misuse and sometimes abuse of power in the state and church.

What I did not, and could not at the time, do was interrogate the narratives that created those assumptions. I could not have perceived that the Christianity that was planted in Africa, whose midwives were the parachurch organisations from Europe and North America, bears the burden of the Western legacy, both in its social outlook and self-understanding. My reading and study of Scripture was nurtured by Scripture Union in high school and the Christian Union at university, and my understanding of the gospel was shaped by Western thought-categories. Two years of theological studies, in a premier evangelical graduate school, did not help matters. I believed that the distinction between ‘evangelical’ and ‘liberal’ was essential to naming the value IFES movements brought to the churches; I believed that all that the African nation-states required to deliver the common good were men and women of integrity. Maybe, if I had taken to heart Adeyemo’s cry, that it was “pathetic that a Church with over 100 years of existence in many parts of Africa is still searching for a theology it can call its own,” I would have considered more deeply African worldviews as hermeneutical frameworks.

I have since learned the power of story in making sense of assumptions and visions, and how we live. Narratives constitute the substructure of our imagination and sense of who we are; they determine our sense of identity and reality; they name the reality we know and that which we hope for. And, like the roots that hold the stem, branches, flowers, and fruits of a tree, they are invisible. Reading some African theologians, who have grappled with these questions, has been a succour for my soul. I resonate with Emmanuel Katongole, that we must interrogate more deeply why Christianity and the churches were part of Africa’s post-colonial malady. I agree with Katongole that the hope lies in finding a “different story that assumes sacred value and dignity of Africa and Africans, and is able to shape practices and policies, or new forms of politics, that reflect this sacredness and dignity.”

Since the realities of chaos, poverty, violence, and tribalism are wired within the foundational imagination of modern Africa, a new future in Africa requires more than skills and technical adjustments to improve nation-state legitimacies and operations. It calls for new stories, a different foundational narrative or narratives that can give rise to new expectations and a new imaginative landscape within which a new future in Africa can take shape. This search for a new future in Africa, which is a search for a different starting point for politics in Africa, must become the subject of a fresh conversation in Christian social ethics.

IFES national movements could make their contribution in this journey of searching for a fresh conversation on what the Gospel teaches about the common good and re-imagine the future of Gospel witness on the continent.